By: Shaun Mustang Jacinto & Paul Angelo Salvahan

Publication: Angelique Inlong

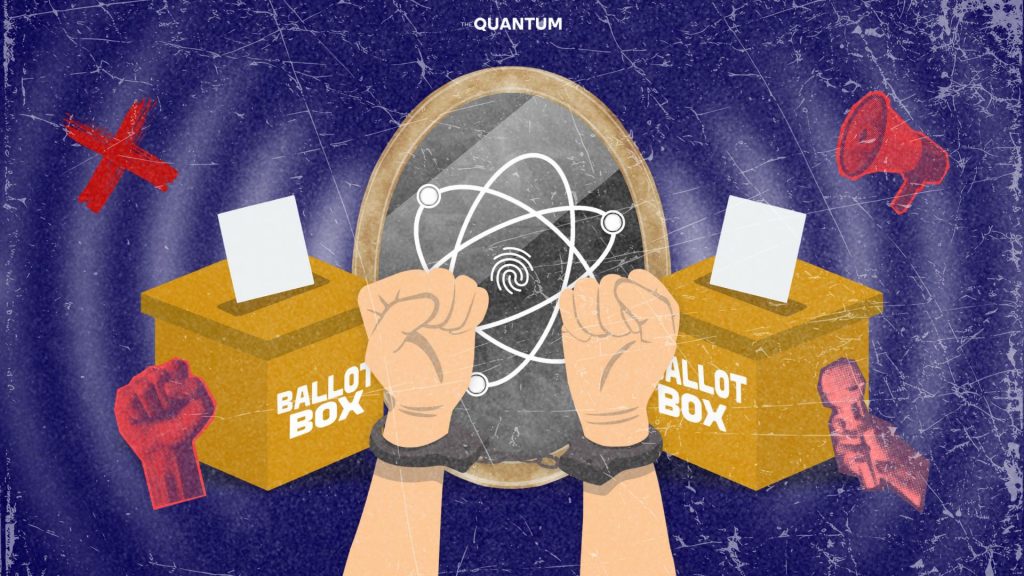

Schools have always mirrored our society. From price hikes to social dynamics, it’s a microcosm of what the ‘real’ world is. School elections, for instance, mimic well the nuances and trends we see in local and national elections.

Ideally, they offer us students a democratic process that gives where they majority selects their supposed rightful leaders. But what happens if that power bears no brawn and intelligence? Would cutting the head of the snake solve the problem, or would fostering an environment unfit for a snake to wreak havoc be a better course of action?

Due to their striking resemblance to larger-scale elections, school elections play a critical role in raising a generation of voters. However, this similarity also implies that the same deep-rooted issues—political dynasties, monopolized leadership, and voter ignorance—are present even at the school level.

One particularly concerning trend is how certain candidates benefit from political affiliations tied to previous administrations. This holds true in Pulse Asia’s last preference survey for the upcoming senatorial election, when familiar surnames dominated the top 14 spots most of which are re-electionists and the rest coming from known political dynasties.

They wouldn’t be able to do this without their own way of deception however, which is why on top of their engraved names in the mind of the people, their delusive campaigning also plays a huge factor to their triumph. Take for example the ‘Alyansa para sa Bagong Pilipinas’ partylist leveraged off of their slate filled of “experienced” candidates who already once held positions in the legislative and local governments.

The perfect concoction that deludes the masses, requiring a blaring wake-up call to break free from these illusions and recognize the minimal impact flashy candidates have made during their time in service. Credit grabbing and unnecessarily lengthy credentials are the shadows that dim the light to this reality.

The very issues that plague national and local elections hide in the underbelly of school elections, reinforcing the idea that our political problems are systemic rather than incidental. Just as in larger-scale elections, school elections tend to favor name recognition over merit, reward performative and populist leaders over genuine service, and create a cycle where the same people retain power. This mirrors the deeply embedded political dynasties and patronage systems that cripple Philippine politics, where elections are less about democratic representation and more about maintaining control.

One clear example that exacerbates this is the “vote straight” culture in school party systems, where students are encouraged to elect an entire slate rather than evaluating individual candidates based on merit. Albeit party affiliations can provide structure, they often serve as pylons for exclusivity, prioritizing alliances over competence. This mimics the way political parties in the Philippines operate, particularly in the party-list system, which was meant to give marginalized groups representation but has instead been co-opted by elite interests.

Just as established names dominate the ballots in national elections, school parties often become monopolized by the same groups, making it difficult for independent candidates or newcomers to break through this chain. This culture discourages critical voting and reinforces blind loyalty over informed decision-making.

The sad metaphor of “musical chairs” aptly describes this cycle of Philippine politics: the same names resurface, ensuring that power remains within the same networks.

It is clear that voter education alone cannot fix an electoral process designed to benefit the powerful. While it is often seen as the key to better election outcomes, education means little when the system itself encourages popularity over substance, exclusivity over inclusivity, and familiarity over fresh leadership.

Without institutional reforms that address elite control, unregulated campaign practices, and voter apathy, educating students on how to vote wisely will not be enough to disrupt the status quo. This is why school elections should not be treated as just mock elections, but as opportunities to demand and practice real democratic principles.

Political change does not begin and end at the ballot box—it must start where power structures first take its form: within the confines of schools. If student elections continue to manifest the dysfunctions of national politics, then we are merely training the next generation to accept corruption, performative leadership, and political stagnation as the norm.

Breaking this cycle demands continuous efforts to demand transparency, hold student leaders accountable, and push for fairer election policies within schools. Change begins at the grassroots level, not just in national government, but in the very institutions where we first learn to engage in politics.